There’s quite a lot of understandable buzz out there about the fact that the former National Security Advisor, the short-lived Michael Flynn, has asked for immunity in exchange for agreeing to testify before a Senate committee investigating the Russia mess. See http://bit.ly/2nTEyjL (“Flynn Offers to Cooperate”).

While this is the stuff that white collar lawyers do all day, it’s pretty darned opaque to the the rest of the world. What exactly does it mean to ask for immunity in exchange for cooperation?

Let me offer the following as a guide:

- The U.S. Constitution makes it illegal for the government to try to elicit confessions from a target of an investigation. The Fifth Amendment provides in part that no person “shall be compelled in any criminal case to be a witness against himself.” Thus, a witness can “take the 5th” and say no thanks when some government investigator comes with a subpoena. Taking the 5th comes with a price, though. Most people, including investigators, believe that you’ve got something to hide if you “Take Five.” They make note of it and file that away in their mental storage cabinet.

- The United States is one of the few countries in the world with such a rule, and it is one of the most cherished principles in our founding document. In most other countries of the world, people can be forced to testify about the matter under investigation, and the prosecution can use that testimony against the person. (Want to know why the Guantanamo prison camp was set up outside of U.S. borders? One reason was so that forced confessions could be used against the prisoners without running afoul of the Fifth Amendment. Dick Cheney was not kidding when he talked about taking us to the dark side.)

- The rule against compelled self-incrimination doesn’t stop the prosecution from talking to the witness, however; it simply stops the prosecution from using the interview as evidence in a case against that witness. So how do they get the witness to talk after he says no thanks?

- This is where the immunity comes in. Suppose the prosecution is really most interested in the witness’ boss, and the witness knows a lot about what the boss has done. In fact, the witness was a co-conspirator with the boss in something illegal. In this situation, the prosecutor or investigator might promise “use immunity”, i.e., an agreement that he/she will no use the interview against the witness, in an effort to elicit damaging testimony against the boss. The “use immunity” effectively serves as a work-around of the 5th Amendment, but one that comes with a cost to the prosecution. If the prosecutor grants immunity too liberally or too early, he/she may have given up too much.

- How does the prosecutor know whether to offer immunity in exchange for truthful testimony? Suppose, for example, that the witness gets immunity and then turns out to be someone who can’t remember a thing, or shades his testimony to help the boss avoid prosecution? If the only case that could have been made was against the witness himself, as it turns out, then the immunity granted was a big, complicating waste.

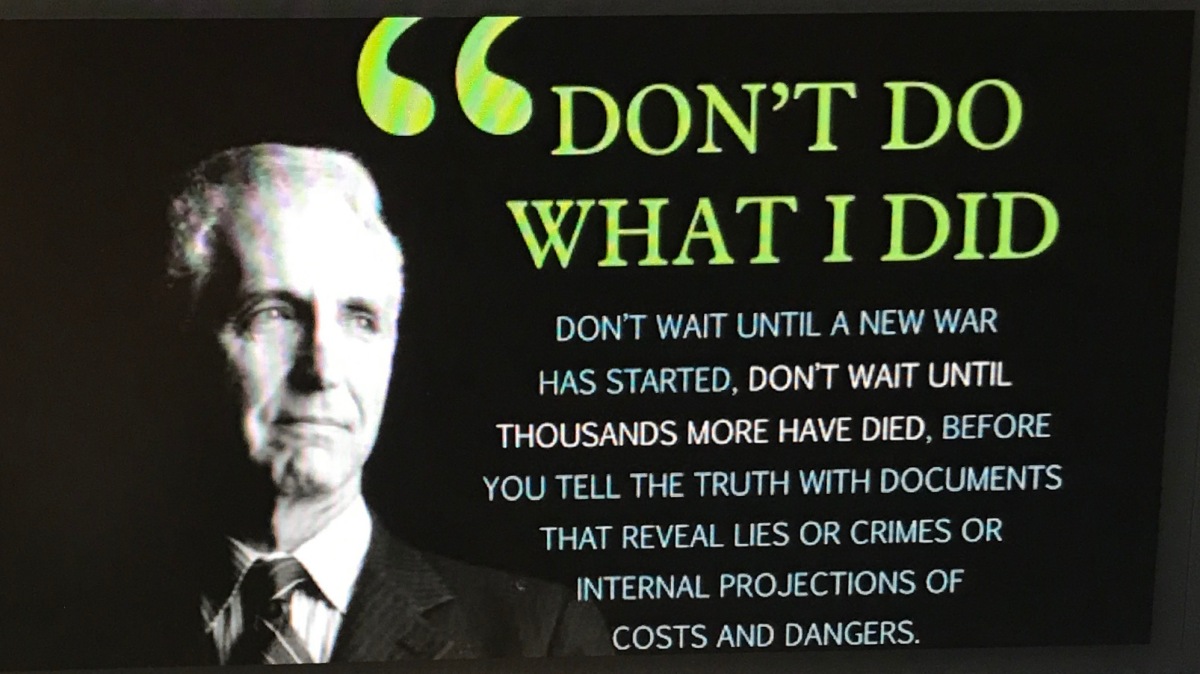

- The immunity granted may also have also made it virtually impossible to prosecute the witness, because the witness will later claim that even though you didn’t use the actual statements against him, those statements “tainted” the investigation by virtue of the fact that the prosecution made “derivative use” of what it learned in the interview. This is why Oliver North’s conviction was overturned and his case ultimately dropped, a precedent that the Senate is no doubt more sensitive to this time around than they were when they offered North immunity to testify over the Department of Justice’s objections.

- To prevent “buying a pig in a poke,” the investigators or prosecutors give the witness and/or his lawyer a “Queen for a Day” letter, which essentially says that we’ll let you come in and talk to us, for this one meeting only, with the assurance that we won’t use the statements against you. In this way, the government can evaluate whether or not the potential testimony is helpful to them or not, say in a case against the boss for example. If it’s not good enough, then they say never mind and don’t offer the use immunity for the actual court proceedings. (In the macho world of law enforcement, it is no accident that the letter is not called “King for a Day.” We’ll hear you out — but only if you put on a dress in front of us.)

In other words, this is the start of a complicated dance between two parties, one of whom wants to know what this guy has to say, and the other of whom wants to know if he can get a better outcome for himself by trading in on his information.

The dance is further complicated by the fact that both branches of Congress have subpoena power and can call witnesses to testify before them at the very same time that criminal investigators at the Department of Justice are conducting their own investigation. It would be naive to think that all this can happen without messiness.

That’s what Flynn is taking advantage of. He’s essentially saying “Hey, I’ve got something good you might want to hear, but you’ve got to sprinkle holy water on me first. Bathe me in the waters of the 5th Amendment and I’ll sing a song.”

It worked for Ollie North.

The Senate is right to move slowly on this. Flynn is a big fish, just like North was. No doubt the F.B.I. and the Department of Justice are already thinking seriously about what laws he may have violated by contacting the Russian government during the campaign and during the transition. They don’t want to see their investigation messed up by a Congressional hearing with all its partisan theatrics, non-lawyerly questions, and offers of immunity. Some argue that the Senate should offer the immunity because we as a nation need answers right now. See http://nyti.ms/2okT5Gn (“Trump is Right: Give Flynn Immunity.”) But this is a trap for the unwary.

Once — and only once — investigators know enough to be clear what laws Flynn may have violated, then they can test his offer to cooperate — from a position of strength. Come on in and be Queen for a Day, Mr. Flynn, and we’ll see what you have to say and see whether it furthers our investigation. Translation: if you have something good on the boss, then we’ll talk.

If they have a solid case against Flynn and signal an intention to prosecute him, this decreases the likelihood that he will dodge and weave as Oliver North did. If they have a solid case against him, only testimony that sinks his boss should be worth the price of immunity.

(The author was an Assistant United States Attorney from 1989 to 1997.)