So what just happened?

Today, April 6, 2017, as predicted, the Senate majority led by Mitch McConnell just “went nuclear” and abolished the filibuster rule for Supreme Court justices, ensuring Neil Gorsuch’s appointment to the Supreme Court and paving the way for easier confirmation of much more controversial Supreme Court nominees in the future. It was a move that Senators on both sides did not want to see happen, but none felt capable of holding himself/herself back from the leap off the cliff.

Why? How did we get here?

In the short run, of course, this was all about Merrick Garland. The Democrats felt that the Republican refusal to consent to the appointment of an eminently reasonable and well respected jurist a full nine months before the end of President Obama’s term was an extraordinary act of aggression and illegality, and they were right. There has never been a price paid for that little coup. The Republicans got away with it, and the Gorsuch opposition was the best the Democrats could think of as punishment from their 48-seat minority status.

If the Republicans cared less about winning, the opposition to Gorsuch and the escalation to killing the right to filibuster might have given them pause. McConnell warned then-Senate leader Harry Reid a few years ago, when the Democrats abolished the filibuster rule for lower court judges, “someday the shoe’s going to be on the other foot, and maybe sooner than you think.” So it is here. Republicans might have paused to wonder whether they will ever be able to block a Democratic nominee in the future. But they do care about winning. A lot. More on that in a moment. So nuclear it went. Mitch just couldn’t pass up a spike, after the perfect set of keeping a qualified nominee off the court for a full year.

Gorsuch looks silky smooth in presentation and on paper. But there is reason for concern about his intellectual points of view, as well documented by Bill Moyer’s recent article http://billmoyers.com/story/senate-democrats-are-right-to-filibuster-gorsuch/. We can expect milder language in Gorsuch opinions than Scalia’s snarky flame-throwing, but the same outcomes. He will be, I predict, a reliable vote for the right, having been groomed and vetted by the Federalist Society for decades. Whatever he becomes, it will be for a long time: He’s 49; Garland was 64 when nominated last year.

Democrats might have paused before deciding to filibuster. From a purely strategic point of view, Gorsuch may turn out to be more center right than far right, and some have argued that since he’s merely replacing Scalia’s already conservative vote, the Democrats should have held their filibuster option for the next, potentially more controversial nominee.

This assumes, howwever, that Trump is going to get another nomination before leaving office (by no means clear, given all the Stay Well cards being sent to Ruth Bader Ginsburg). More important, it would have signified that the Democrats had no answer and no anger in their bones about the fact that this seat was stolen. So this risky, potentially-backfiring filibuster is mostly about symbolism, politically speaking.

From a legal standpoint, there can be no question that Gorsuch will be more conservative than Garland, who was not at all a lefty. Garland would have moved the court slightly more to the center. Gorsuch will keep it leaning right.

But let us go back to the win-at-all-costs theme. I’ve noticed over the course of my lifetime quite a few political battles that the Democrats have lost where one might have asked “What if they had played the game as hard as Republicans?” What if they employed some of these ‘ends justify the means’ tactics the Republicans keep using to keep a stranglehold on the levers of power, despite the fact that the demographics of the country are moving against them?

What if the Democrats had fought harder in the recount election of 2000? What if Obama had told McConnell last year: either vote on this nominee or I’ll take the position that you’ve waived your right and appoint him on an interim basis?

Democrats, in my opinion anyway, seem less willing to precipitate a crisis to get what they want. Republicans, it seems, mind this a lot less if it means they win. Perhaps this is grounded in political philosophy: if you believe, fundamentally, in a communitarian world view, doing violence to procedural rules is deeply offensive to the ability to get along. If, on the other hand, you believe in a libertarian world view, rules are meant to be challenged — early and often. Kill the administrative state, as Steve Bannon would say. Who cares? Maybe there’s some other force at work here that I can’t see. I know, though, that I am not alone in feeling like one side keeps fighting with one hand voluntarily tied behind its back.

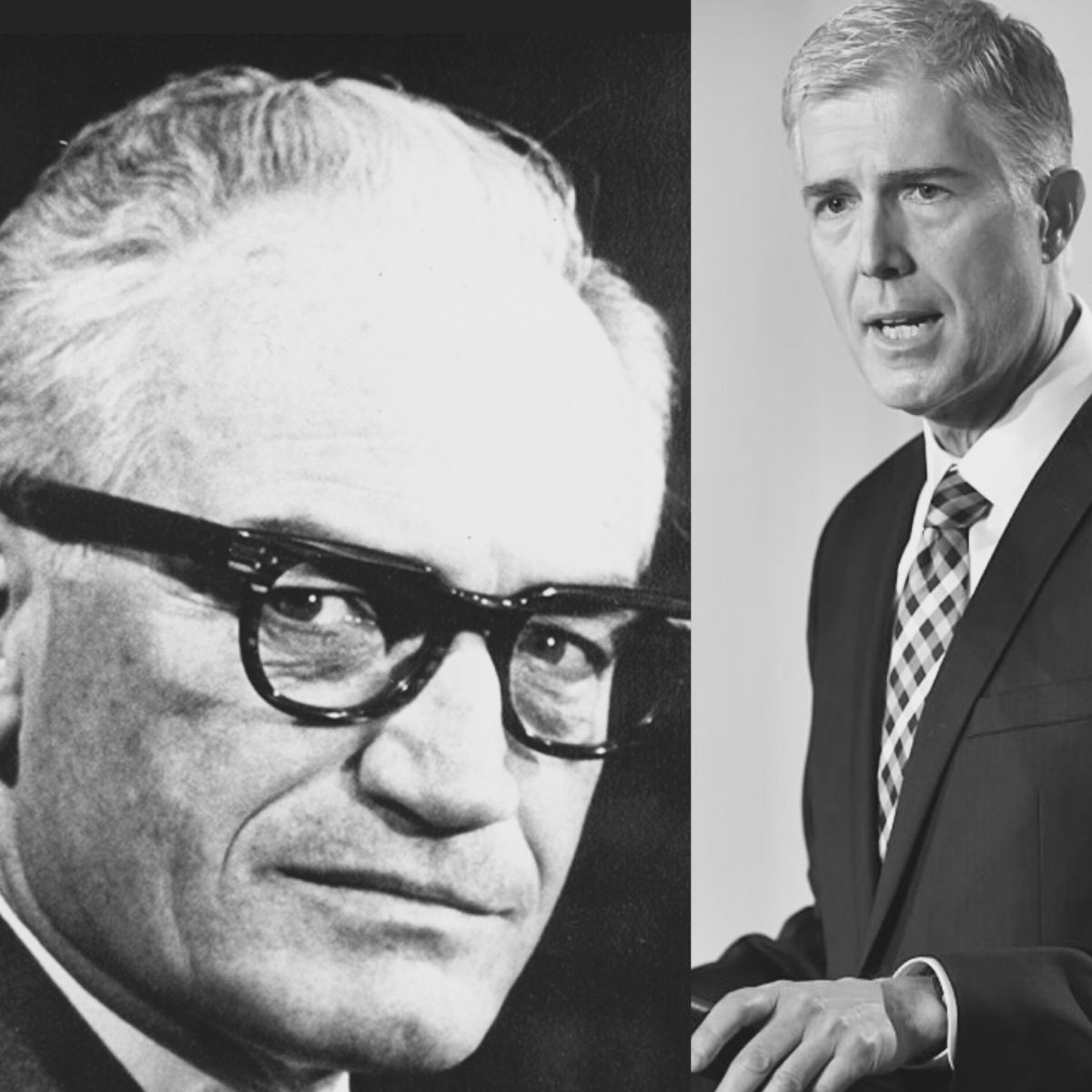

It takes me back to a controversial statement made on the floor of the Republican Party nominating convention of 1964. Barry Goldwater, the intellectual grandfather of today’s Republican Party, said the following: “Extremism in the defense of liberty is no vice.” That’s one of those lines you have to repeat, and say slowly, like the line of a poem. Did he really mean that? Did he mean any form of extremism?

While Goldwater went down in a landslide, his political philosophy survived and became the lifeblood of the Republican Party. As the party added Nixon’s racist “Southern Strategy,” and Reagan’s anti-government libertarianism, and the evangelical and anti-intellectual reaches of the W. Bush presidency, what remained constant was a certain commitment to winning, by whatever means it took. Run the Willie Horton ads — what the hell let’s just win this thing.

How else to understand what we’ve just witnessed, a history-making change to the Supreme Court’s balance? How else to understand the litigation strategy to ask the Supreme Court to decide the election of 2000, when the Constitution clearly requires that the House of Representatives decide elections if the electoral vote is disputed? (Yes, it really does say that.) How else to explain Ted Cruz’ commitment that if Hillary Clinton had won the Presidency, he’d have left the Supreme Court seat vacant for a full four years? How else to understand the directive of Mitch McConnell to his Senate colleagues on the day of President Obama’s inauguration, that the Republicans would fight his Presidency — no matter what policies he espoused?

A Senate Leader who who say, despite Obama’s comfortable margin of victory in both the popular and electoral votes, that his “number one job is to make sure Obama is a one-term President” is a man who cares much more about winning than about process.

Yes, Goldwater lives. His spirit of extremism has carried forward to today. Little did anyone at the time foresee that in the ashes of that landslide defeat lay the fertilizer for the political principle that there’s no such thing as an unfair win. Only results matter. It’s not at all clear that it’s liberty they’re fighting for, as Goldwater suggested, but it is more clear than ever that they’re willing to go to extremes to get what they want.